Getting back to first principles

I was recently introduced to the concept of Zero-Based Budgeting, which made me consider teaching choices from a ‘zero base.’

Why bother?

ACSL points out here that, although average teaching time in England (20 hours) lines up with the international average, we spend more time on preparing lessons (7.8 hours compared to a median of 7.1 for high-performing countries), marking work (6.1 hours compared to 4.5 hours) and admin. (4 hours compared to 3.2 hours); while research reported here finds that teaching is consistently among the top three most stressful professions because: “The hours are long and antisocial, the workload is heavy and there is change for change’s sake from various governments.”

Joe Kirby argues that reducing workload takes a “shift in ...mindset” to focus on ‘impact-effort’ ratio. And, as he points out here, “Teachers who aren’t exhausted teach better.”

Ideas to improve your ‘impact-effort’ ratio from Michaela School

Getting back to core purpose from Durrington High School

James Theo discusses the concept of Opportunity Cost here

Although James Mannion argues here that Opportunity Cost is “increasingly being used as a prima facie argument against entire educational practices, regardless of context.”

We need to think ipsatively: Education doesn’t lend itself to ‘having it all’ any more than motherhood.

8 Things to Ditch

1. Meaningless lesson activities

First principle: Lessons should promote permanent mastery

At Northern Rocks 2015, Stephen Tierney advised, “Don’t plan lessons, plan learning.” Every lesson activity should be judged according to how effectively and efficiently it promotes permanent mastery.

In Measuring Teacher Effectiveness, Muijis found that time on task was one of the most important influences on achievement, while in What if everything you knew about education was wrong? David Didau argues that, “spending time proving something has been learned is time that could be better spent learning stuff.”

Think ipsatively: copying lesson objectives, starters, plenaries, group work, engagement, variety, collaboration, flashy presentations, discovery activities, IT skills, progress-checking and what Joe Kirkby dismisses here as “whizzy/ jazzy nonsense” may seem desirable, but they are not preferable to permanent mastery.

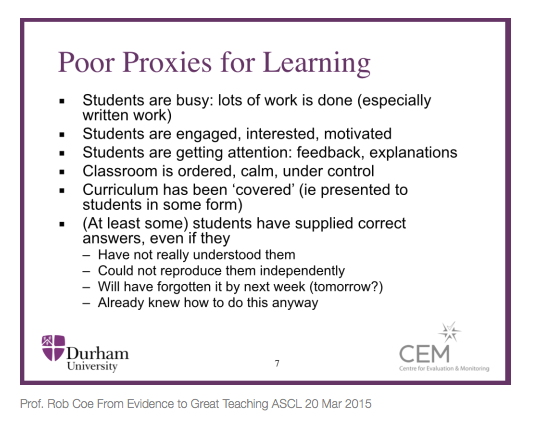

And avoid proxies for learning:

Time-efficient strategies

- Time Saving Pedagogy @ Love Learning Ideas

- Developing a common-sense approach to Teaching and Learning @Teacher Toolkit

- Memory platforms @Reflecting English

- Metacognition: teaching students to learn the thinking @johntomsett

- Sequencing lessons @Reflecting English

- Permanent Learning @Love Learning Ideas

2. Meaningless Reports

First principle: Parents have a clear picture of their children’s progress

ACSL points out that, “what matters is that systems are used effectively to support and protect time for professional dialogue” rather than paperwork as “an end in itself.”

Think ipsatively: are detailed reports preferable use of time? Would parents gain greater insight from looking through their children’s work or by online access to subject and behaviour data?

3. Meaningless marking

First principle: Marking should lead to students thinking hard about their work and teachers thinking hard about their teaching

Michael Tidd argues here that, “the most powerful and valuable feedback occurs in the first few moments of looking at a piece of work. Every moment spent thereafter on combing through, adding red pen, or forming detailed comments, is likely to produce a diminishing return [and may mean we] miss the most important things that would re-shape our own teaching.”

Think ipsatively: However desirable extensive marking may seem, students don’t think hard about their work if marking:

- States the obvious

- Proof reads work for them

- Corrects/ improves work for them

- Does the thinking for them

More on this at Two stars and a bloody wish!

Joe Kirby describes marking here as “the ultimate non-renewable resource,” so consider ways of making it renewable, such as Taxonomies of Error.

Time-efficient strategies

- Meaningful Manageable Marking @Love Learning Ideas

- Reclaim your Marking @Love Learning Ideas

- What could happen to the work that we don’t mark @Benneypenyrheol

- What not to mark @Teacher Toolkit

4. Meaningless meetings

First principle: Meetings need a useful point

This could include: generating ideas, sharing opinions, discussing ideas, reviewing or planning activities, making decisions or agreeing actions.

In The Jigsaw of a Successful School, Tim Brighouse quotes research that schools are successful when teachers:

- Talk about teaching

- Observe each other teaching

- Plan, organise, monitor and evaluate their teaching together

- Teach each other

Think ipsatively: What use of limited time together will have the greatest impact?

5. Over planning and resourcing

First principle: Teaching should promote permanent mastery

Kris Boulton wonders here, “Have we got teacher professionalism all wrong? What if our expertise lies not in planning and resource design but in knowing about the best resources, making informed, intelligent choices about what to use and when?”

Think ipsatively:

Creating resources is more enjoyable than marking work but is it a more effective use of time?

Are individual lesson plans as effective as carefully crafted medium term plans focused on sequencing learning effectively?

Time-efficient strategies

- Sourcing effective textbooks @Bodil’s Blog

6. High stakes stand-alone observations

First principle: Observation should improve teaching

Robert Coe explains the unreliability of lesson observations here. Nick Rose writes here that, “for summative measures of effective teaching to achieve... rigour and reliability they would become so time-consuming and expensive that the opportunity costs would far outweigh any benefits.”

At Northern Rocks 2015, John Tomsett suggested asking the question, “How would you like to be observed to help you best develop your teaching,” and building scrutiny of the work produced in the observed lesson into the process.

Think ipsatively: Formative observation is more desirable than summative observation.

Life without observation grades

7. Meaningless CPD

First principle: CPD should improve teaching

Developing Great Teaching finds that professional development opportunities that are, “carefully designed and have a strong focus on pupil outcomes have a significant impact on student achievement.”

David Weston criticises here, “one-size-fits-nobody, whole staff, one-off lectures.”

David Jones points out here that, “Over the last 10 -15 years professional development in many schools has tended to follow generic pedagogical discussions and in many cases been imposed by senior leaders, involving perhaps one-off events with expensive external delivery and most definitely will have sung the Ofsted tune or current educational tune of the day.”

Think ipsatively: reducing the CPD budget may be desirable but is it a false economy?

Effective Strategies

- Coalition CPD @Meols Cop High School

- A model of effective CPD @Improving Teaching

- Adding debate to CPD @Whatonomy

8. Constricting Meta-beliefs

David Didau champions open-mindedness in education. In What if everything you knew about education was wrong? he introduces the concept of the ‘meta belief,’ described here by Daniel Willingham as a belief has become, “the prism through which we view the world... We fail to think about these beliefs and instead think with them.”

Timperley warns here that, “A collegial community will often end up merely entrenching existing practice and the assumptions on which it is based.”

Similarly, James Theo argues here that inconsistency is part of professional development.

Challenge yourself

- On group work @tombennet71

- On grouping @Esse Quam Videri

- On seating plans @The Learning Spy

- On display @The Learning Spy

What is false economy...

Failing to invest time in teacher expertise

It can’t be merely correlation that Singapore, one of the highest performing countries in the world, invests 100 hours a year into teachers’ professional development.

Timperley advises here that, “to make significant changes to their practice, teachers need multiple opportunities to learn new information and understand its implications for practice.”

An ASCD Blog suggests replacing ‘best practice’ with ‘effective practice:’

- Teaching is more than “a simple collection of independent and replaceable parts... Effectively implementing new practices requires extended practice-based professional learning as well as continual study and refinement of teaching.”

- Best practices can “uncouple learning goals from instructional methods... Different teaching methods are more effective for some learning goals than others... The better question is this: For this learning objective, for this group of students, at this point in the academic year?”

- Best practices “focus on activity instead of achievement.”

- “Professional development focused on continual improvement of teaching is more effective than imitation of best practices... Better teaching doesn’t come from imitating what star teachers do. Better teaching is built by steady, relentless, continual improvement.”

Similarly, David Didau warns here that, “Teachers often exhibit mimicry – copying what they see others doing – but without trying to develop the understanding of the expert teacher.”

Amjad Ali suggests Try, refine, ditch...? as a model for developing teachers’ professional practice:

Harry Fletcher Wood points out here that, “to improve, teachers need the chance to see good teaching.”

Dan Brinton suggests using Practice Guides to communicate evidence-based advice that is:

- Actionable by practitioners

- Coherent

- Explicitly connected to the level of supporting evidence

Strategies

- Educational Ideas all teachers should know @Headguruteacher

- Set up an Edu-Book Club @Class Teaching

- Ten research-based principles of instruction for teachers @Belmont Teach

- Five Psychological Findings every teacher should know @ImprovingTeaching

- Practice guide on improving student learning @Belmont Teach

- Put the spotlight onto classrooms @Improving Teaching

- Follow a Blog of the Week: Durrington High School and Belmont Community School have excellent ones